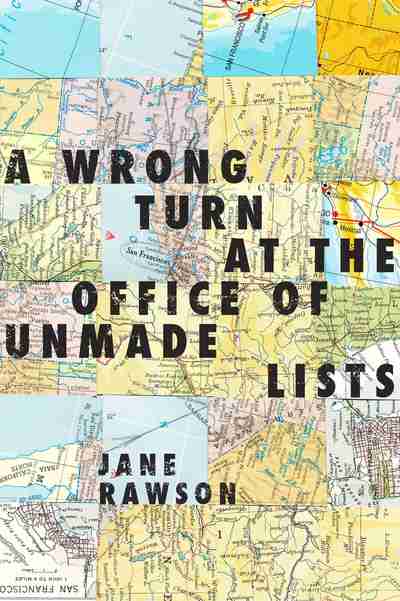

Jane

Rawson’s 2013 novel ‘A Wrong Turn At The Office of Unmade Lists’ defies easy

description. Its genre is indefinable, the plot ambitious, and the characters

unusual, and yet familiar at the same time. It is no surprise then that this

release by small press publisher Transit Lounge was recently awarded the 2014

MUBA, ‘Most Underrated Book Award’ judged by a collection of Australian indie

publishers. The complexity of material in the novel deserves close attention,

and hopefully the publicity surrounding the win will bring Rawson a wider

audience.

‘A

Wrong Turn At The Office of Unmade Lists’ begins in the future, a fairly bleak

Melbourne, where the rivers are polluted, survivors live in humpies, and the UN

patrol the camps giving aid to those trying to eke out a living. We meet Caddy,

who has lost her home and her husband; she sits in a bar by the river,

negotiating deals with the street kids around her, and musing on the short

story she has been writing while she whiles away the hours:

‘A

Wrong Turn At The Office of Unmade Lists’ begins in the future, a fairly bleak

Melbourne, where the rivers are polluted, survivors live in humpies, and the UN

patrol the camps giving aid to those trying to eke out a living. We meet Caddy,

who has lost her home and her husband; she sits in a bar by the river,

negotiating deals with the street kids around her, and musing on the short

story she has been writing while she whiles away the hours:

‘At

the Newell settlement someone had been cooking fish on a fire. It smelled good,

but she’d learned a long time ago that she didn’t have the constitution for

river fish. Instead, she’d pulled a pack of oat bars from her humpy. Man, she

needed to find some work’.

Caddy’s

mate Ray is also trying to survive in this grim world, and he enlists the willing

Caddy to sleep with clients who still have money from some undisclosed source

of business. Rawson paints the future Melbourne evocatively: the environment is

ruined, disease is rife, the Internet is still ruling people’s lives but is

essentially useless in providing what everyone wants, food and fresh water.

Rawson’s vision of the future is depressingly easy to believe but at the same

time vividly imaginative:

‘These

days, navigating the smeared platforms and dismantled escalators of the City

Loop settlement stations was a much bigger worry than terrorists. Thousands of

people lived in the three underground stations, with no water, no ventilation

and noone clearing anything away, ever. Elsewhere in the city settlements took

care of themselves, kept things clean, looked out for each other. But for some

reason the City Loop had attracted the worst down-on-their luck transients, the

most mentally ill, the creepiest scanners, the fallen-from-favour cops and

bouncers, tough guys and reprobates always assuming someone else would clean up

after them, never doing a thing for themselves.’

We

exist in Caddy and Ray’s world for a while before Ray takes a detour and

stumbles across some printed maps amongst the junk piles and they pique his

interest. And so it is the maps that lead us into the strange world of the ‘suspended

imaginums’, and we are to learn through a mix of Ray’s travels and a sub plot

concerning two new characters Sarah and Simon, that we have entered Caddy’s unfinished

short story. Rawson enters meta territory, and Ray’s introduction to the Office

of Unmade Lists with its curious employees is reminiscent of the film ‘Being

John Malkovich’ or the absurdity of classic ‘Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’:

‘’No

maps, bud. Look, this is Shadow Storage and Retrieval. Head over that way’, she

pointed left, ‘and you get to Suspended Imaginums. Past that, Imaginum

Incubation. To your right, Odd Socks, then Tupperware Lids, the coffee shop and

gift store, then Partially Used pens, then Remotes, then Lost Oddments. Unmade

Lists have just set up their own Office, but they’re still waiting on funding

for equipment’.

The

dialogue in this section is witty and droll, perfect for the scene Rawson is

setting. The plot becomes more complex, the narrative moves between third and

first person, and time moves between past Australia and future Australia. Rawson

is ambitious in her structure and voice, whilst maintaining coherence and pace.

I did think the earlier sections in future Melbourne were more confident, less

dialogue driven and more purposeful. However, the latter sections no doubt were

what captured the attention of the MUBA judges: their scope and imagination

make this an unusual and worthy read.

http://australianwomenwriters.com/